In the 2025 season, Laura Muller will be the first-ever Formula 1 race engineer for the driver Esteban Ocon of team Haas. The German engineer, who started her career in motorsport in 2020, was promoted last week from her previous position as a performance engineer.

Although this is a single move and a single appointment, it is a significant one. It is a sign of a (even so slow) changing attitude in the prominent male-dominant environment. It also cracks (even on a tiny scale) the common stereotype that women do not like motors or are not good at anything related.

This choice is one of the latest “first times” that, unfortunately, do not yet correspond to the fact that STEM studies remain less attractive to girls and young female students. And physics, engineering, and computer science (PECS) even less—resulting in those fields having the lowest percentage of women graduates worldwide.

It may not be the only reason, but since not many female students pursue those education paths, women in general remain overly underrepresented in those careers, from junior positions to the top. In other words, they are left out of today’s better-paid jobs, occupations with better growth opportunities, and those in high demand.

A further, even if partial, proof comes from LinkedIn’s “Job on the Rise 2025”. The platform indicates that Artificial intelligence is leading the change in occupations this year, thanks to the skyrocketing demand for AI Engineers and consultants, AI Researchers, and Community planners. «AI & data are the fastest growing skillsets in demand, closely followed by networks & cybersecurity, and technology literacy.» And that up-skilling is essential. «59 out of every 100 workers will need training by 2030 to stay competitive.»

The elites vs the rest. Equity to the test

Even though women globally make up over half the students enrolled in tertiary education, in 2023, according to Unesco, they still made up 35% of the graduates in scientific fields, with no progress recorded in that sense over the past ten years. Unsurprisingly, the number of those choosing one of the PECS fields shrinks further.

According to a study published on Science in November, the already wide gap, in some cases, has even grown in 20 years. The analysis conducted by the researchers from New York University*, considered over 34 million graduates in the United States from 2002. They found that overall and across all schools, in 2022, men earned a degree in physics, engineering or computer science at 4.4 times the rate of women. With a very slight improvement from the 4.6 rate registered at the beginning of this century.

However, looking at the institutions by their level of selectiveness (mostly from the maths SAT scores registered among the admitted students), the difference between elite institutes and all the others is evident. Those very few at the top, admitting only students with very high scores, have almost reached gender parity among graduates.

Conversely, everywhere else, then in most schools nationwide, the gender gap grew. To the point that in the places with the lower access levels of maths that generally serve students from disadvantaged backgrounds, men earned those degrees 7.1 times as much as women. More than double the 3.5 ratio recorded in 2002.

Even if the authors themselves admit, «We don’t know whether similar patterns regarding university selectivity exist internationally,» they also repeat a stark truth. «Women are severely underrepresented in physics, engineering, and computer science fields around the world,» making up only 28% of the global STEM workforce and only 22% of artificial intelligence professionals. With all that means both for equality, women’s empowerment and opportunity for economic independence.

The stereotypes begin early

According to OECD data, the percentage of female students choosing a STEM education reached 31% in 2024. At the same time, the women who decided to pursue a degree in education, health, and welfare represented 75% of the total.

Of course, not always a degree leads to a career in a specific field. But it is no surprise that, in general, women held less than a quarter of sciences, engineering, and ICT jobs and occupied an estimated one in five tech positions in companies. They were 26% of the employees in data and AI, 15% in engineering, and 12% in cloud computing in the world’s largest economies.**

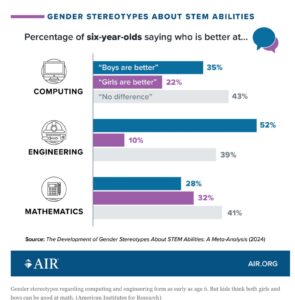

Indeed, many factors limit the appeal for young women in these subjects. From generalized lower access to technological tools to the role played by gendered social conventions. Even if many studies have given mixed results on the impact of stereotypes on girls that keeps them to access those types of education, findings published in the Psychological Bulletin (conducted on 145,000 children from 33 nations) evidence that

Indeed, many factors limit the appeal for young women in these subjects. From generalized lower access to technological tools to the role played by gendered social conventions. Even if many studies have given mixed results on the impact of stereotypes on girls that keeps them to access those types of education, findings published in the Psychological Bulletin (conducted on 145,000 children from 33 nations) evidence that

- by the age of 6, kids already see girls as worse than boys at computing and engineering;

- when girls grow, their biases about boys being better at STEM increase

- an attitude that can further limit their aspirations toward the fast-growing tech field (the so-called dream gap).

Biases that, as the study highlights, are often baseless. «Math stereotypes are far less gendered and often assumed, especially when compared to the stark male bias for computing and engineering».

Little steps forward

Despite the many challenges of exposing girls and young women (as well as boys and young men from more disadvantaged areas) and of opening more opportunities for them to discover STEM and PECS, not all is lost. Generally, there is better awareness. Some more available role models, many of whom are also at hand. And a somewhat easier access to learning. This is also thanks to specific initiatives like Il Cielo Itinerante in Italy or, on an international scale, the not-for-profit Girls Who Code.

We cannot expect an immediate shift. The change needs time and funding. If that was not enough, plans to include more girls in sciences are being put on hold or even cut due to the worrying tendency to reduce D&I efforts seen in the last months.

Yet, bridging the gender gap in these fields is critical to creating a more inclusive and future-ready global economy. «The global information technology industry, for example, – reads a recent article published by the WEF – is worth trillions of dollars and is expected to continue to grow by up to 8% per annum in the years to come». Meanwhile, the disparity among men and women in these fields, «if left unaddressed, will compound reskilling challenges that are already expected to cost G20 countries more than $11 trillion over the coming decade.» Regardless the fact that «evidence shows (also) that a world that invests in women in STEM will be a world that innovates faster and solves problems more effectively.»***

—

* “An institution-level analysis of gender gaps in STEM over time” by Joseph R. Cipian and Jo R. King was published in Science in November.

** Data (2022) reported by the 2024 Unesco GEM Gender Report.

*** As Ebru Özdemir, chair of the Limak Group, in: “Why it’s time to use reskilling to unlock women’s STEM potential”, WEF blog.

***

Alley Oop’s newsletter

Alley Oop arrives in your inbox every Friday morning with news and stories. To sign up, click here.

If you want to write to or contact Alley Oop’s editorial team, email us at alleyoop@ilsole24ore.com.